SHUSHING THE LLAMA

I’ve learned some very tough lessons in the past few weeks. Not about life*, but about my own grasp on my own ability to handle threat.

(*The adage ‘sh*t happens’ has its place in neuropsychology as well as everywhere else in the universe!)

It’s been a humbling experience and yet one that – if I can turn it around- could lead to better things for others. So. Firstly, no one died (important to get that out there straight away for those of us in the trauma world). But a bit of my dignity and naivety has.

As many of you may know (and if you read my personal story in the magazine link in my first blog), it’s fair to say that there is a trauma blueprint in my brain that is not going anywhere. In recent months this has been wildly activated. The immediate threat is now contained but the damage I have caused to myself and those I love has been huge.

Understanding this more clearly could take all our trauma resilience work up a gear.

Everyday life brings threat in Emergency Response. The blindingly obvious threat is the continuous alarm of emergency situations and criminal activity or disorder (when it comes to policing). Thanks to the genius of my former boss and dear friend Prof Brendan Burchell, we now can see the less obvious threat in numbers with data demonstrating a clear association between experiencing management-related issues and developing Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. So many of us in the field also hear snippets and catch glimpses of some very dark thoughts when we support those under the threat of investigation or legal action or who are in more personal destructive relationships with others from whom they can see little escape.

Threats aren’t all about car chases and criminals. Threats come from how people treat us in what we need to be our ‘safe place’. Be it our home or our work, if our base becomes the very thing that threatens us (when it should be the place to which we retreat from outside threat), our brains will struggle.

Mine did as a child. An infant. A teen. And more recently a (wannabe) grown up.

When this happens at work in Emergency Response, this is proper risky. What makes it more risky is that folks will in the main just try and ‘get through’. They don’t have the time to (as my fave colleague Lee said in a recent post online stop and breathe. If we can’t feel safe enough to pause, we can’t get the breath or the resolve to do what we need to – either to make ourselves safe or to temporarily adjust to the threatening conditions.

I didn’t. I tried to, because I teach this stuff and I know all the clinically sound techniques and all the ways to steer the brain. But I missed a trick. I missed the first and only line of defence: self-compassion. As soon as I went to try and get a hold of my anxiety, there was this voice in the back of my head saying, “You shouldn’t have to be doing this, you should have a hold on this, you should be better than this”. And then this ‘tough Jess’ automaton would stroll up to the situation and distract me from caring about myself -and so, I would blindly walk into the next crisis, just a little bit more stunned and depleted than before. With that, old habits decided to chuck a little bit of shame and self-loathing in for good measure.

So, yeah. I’ve been great company. Dissociating from people. Crying a lot. Giving advice with one had and hurting myself the other. All the skills and insight and unfathomable love and support anyone could wish for right there...and did I benefit from them? No.

How can this help anyone? How can I ensure I learn from this? What IS it that happened here?

What happened was I needed to be a little more savvy about this deeper trauma circuitry and to be more forgiving of myself for having it. The next step is to look back and ask myself:

What were the ‘tells’ in my body and what were the thought patterns that could have intimated to me that a deeper threat response was being activated?

Looking back, was there any way I could have hesitated (even just for a milli-second) before reacting to some perceived threat from the people I love and the very people who could have helped?

These are important questions from which to build future resilience. That said, there were very good things, things that I did boss (for the record):

· I set myself up a plan for any sense of panic that I did foresee (simple go-to’s for me are loud metal music and getting outside in fresh air)

· When I caught myself defaulting to disproportionately worrying about things I couldn’t control I congratulated myself with a secret and discrete thumbs-up-to-me

· I reminded myself that everything is transient and that this is one phase in an experience from which I will emerge a better human as a result (even if it takes a while)

· If all else failed, I’d zoom up in my mind’s eye and look down on myself and my situation from the sky or I’d think about nature or something awesome to put the threat in a bigger pot of wonder. By doing this, the threat didn't disappear, it just was in a more realistic perspective.

Most of these things are in Chapter 4 of my book, I know, but when you see the words, it’s not the same as feeling the feel -and sometimes you just have to tune in to your own body in that very personal, unique moment and come up with your own approach. Sure, it will likely benefit from coming out of what we know from things like resilience training, but it will need to have our very own stamp on it, our own trademark on it, for it to become our own resolve.

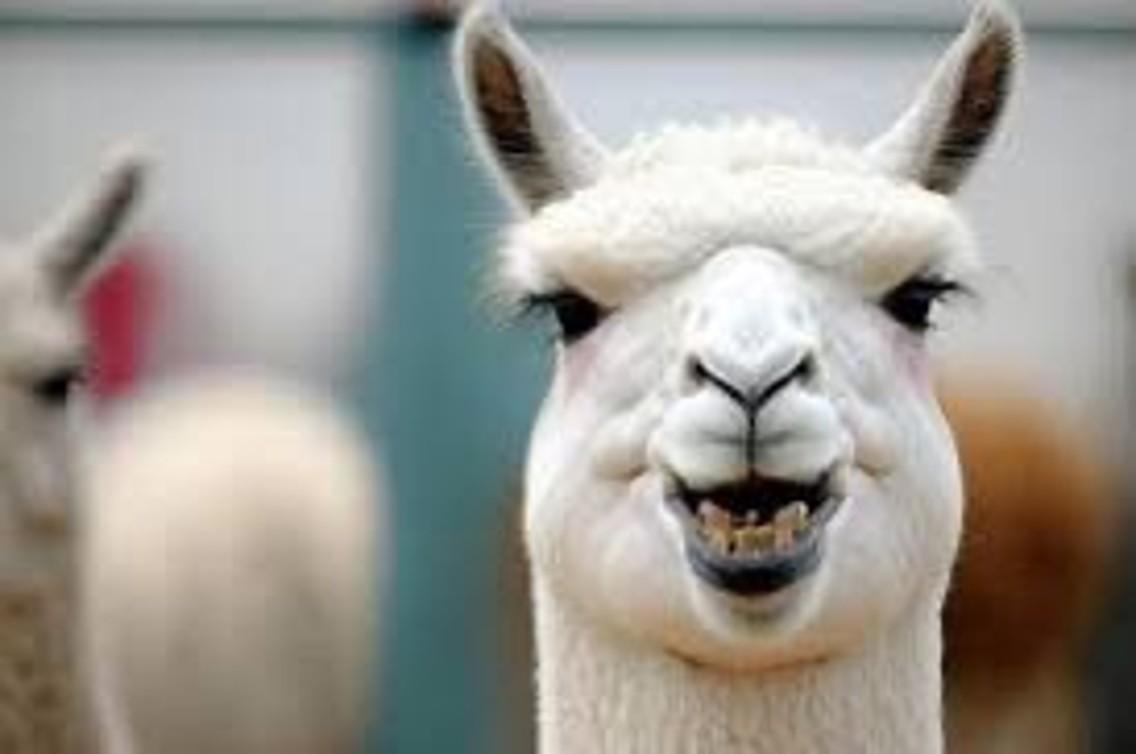

So, my intention for now? To urge you to do one thing I didn’t and I want to try: and that is using very subtle humour as a means to bring down a disproportionate (or as the text books say ‘environmentally inappropriate’) sense of threat. If deep down we know that a threat is overwhelming and yet it absolutely does not need to be as strong as it feels, we can borrow from my favourite neuro trick : The F word and the C word*. That is, to exploit the simple reality and scientific fact that the brain cannot feel funny fluffy stuff if it is taking on angry harmful stuff (and vice versa). So if we force it to catch a glimpse of something even slightly amusing, we cannot feel a threat at the same time.

My suggestion, my quick win: when we sense that there is a massive, overbearing, way-too-loud alarm, we bring to mind our own just as huge, over-smiling, in-your-face llama.

Just that.

From me to you, human to human: may your alarm bell always bring its own llama.

Try it. What do we have to lose?

Jess x

*The infographics posted through The University of Cambridge were funded as part of the Trauma Resilience project sponsored at the time by Police Care UK